The following is adapted from a recent talk.

I was driving my 9th grade son to school last week. It’s always a great time for us to talk, often confessional in nature, when he shared: “We have a new school policy that our teachers have to tell us when their lesson is AI generated. My teacher began class by letting us know that the entire lesson was AI generated, and that she didn’t change a single thing.”

He then added, “So I didn’t feel bad about turning in my entirely AI-generated homework. In fact, I didn’t touch a thing!”

Sticking with my kid’s school policy, I should let you know this whole piece is entirely AI generated. I didn’t touch a thing.

I’m kidding, of course. But the tectonic transformation is real.

I invest in edtech, but I didn’t think we’d be here this fast. AI is already widely used in our schools; it is the fastest growing technology to impact education that I’ve seen in my lifetime. Its adoption is much faster than the last major platform shift in our schools: internet-connected classrooms that expanded over a period of about 10 years.

But as promising as this tech is, the human connection between teacher and student remains the most powerful lever for learning.

Pivoting from Teaching to Investing

When I was 21, I began my career as a public school history teacher. I taught for seven years, then completed my master’s in teacher development. For the next nine years, I learned the craft of venture capital at an organization called NewSchools Venture Fund. There, I was lucky to learn from some of the best investors in Silicon Valley – John Doerr and Book Byers.

For the last decade, I’ve been leading Reach Capital, an early-stage fund I co-founded that invests in learning, health, and work. We’ve invested more than $500M in over 160 companies.

I spend most of my time listening to pitches from education founders, and we are often the first capital in and we work closely with our founders. I pivoted from teaching to venture capital because, as a consumer, I had access to cutting-edge technology that helped me shop and bank online. But as a teacher, doing one of the hardest jobs around, I had truly archaic tools: green grading books, a file cabinet of yellowed worksheets…

I began to explore why we didn’t have consumer-grade technology in our schools, and I learned that venture capital was behind many of the best technology companies in the world. However, there was no capital for education technology. What few companies were out there, were educators who boot-strapped solutions for their own needs.

Snapshot of the American Teacher

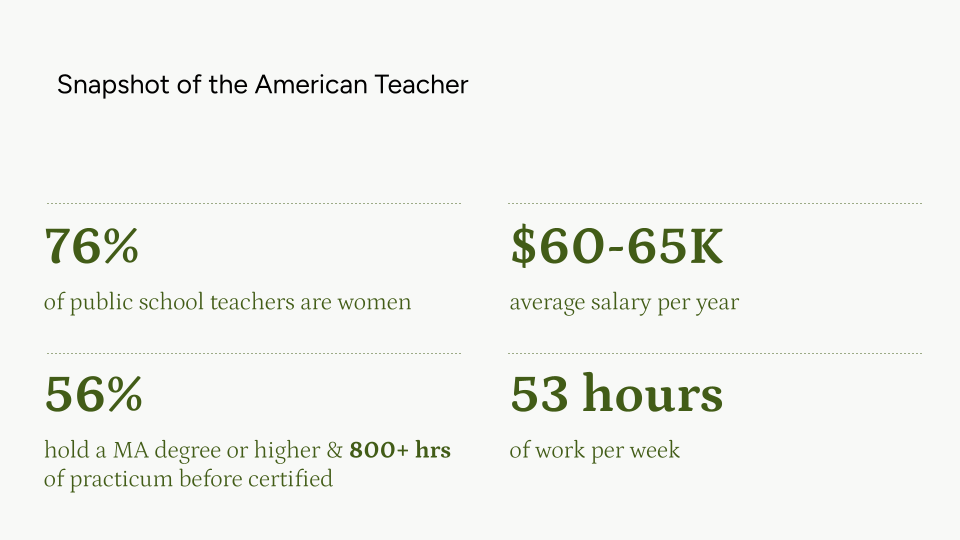

American teachers today are educated, underpaid, and significantly overworked.

About 76% are women, and more than half hold master’s degrees or higher. They earn, on average, $60K-65K per year, working around 53 hours per week — 32% more than the average worker. And this doesn’t include the 800 hours of practicum they need before getting certified.

Teachers have incredible dynamic range, a breadth and depth of skills from technical to creative. It’s not surprising that some of the best business leaders have teaching backgrounds, like Reed Hastings, Jack Ma, Howard Schultz, and Jeff Bezos.

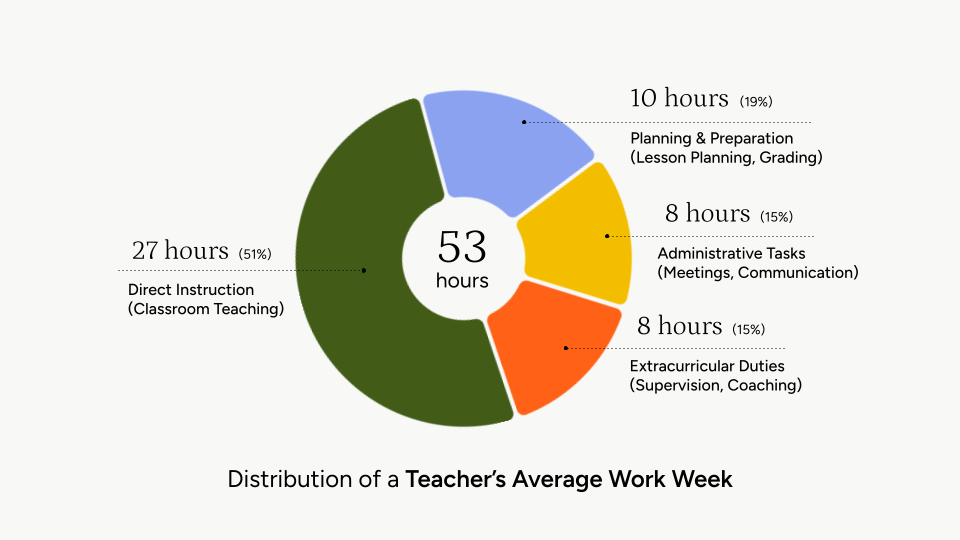

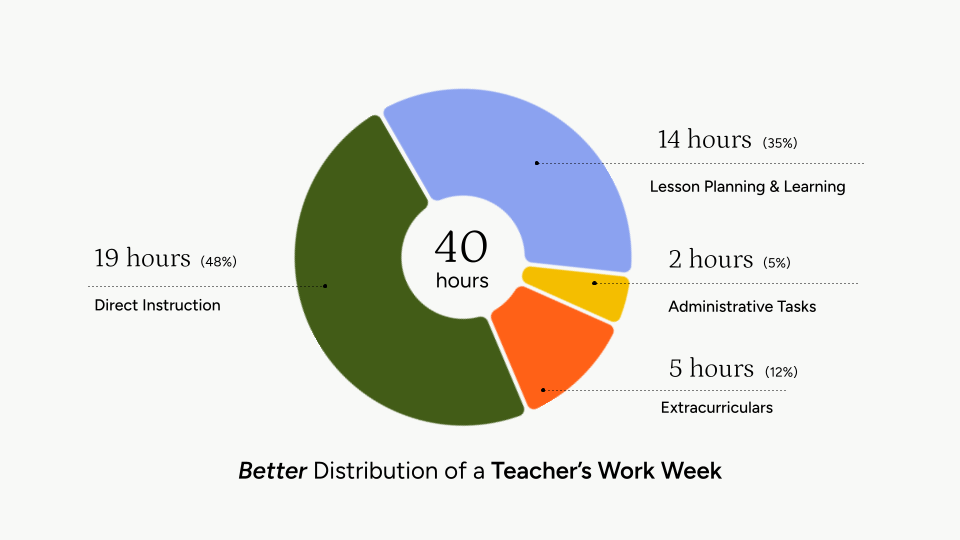

When it comes to their day to day, about half of a teacher’s day is spent directly with students: teaching, mentoring, and engaging them. In fact, American educators dedicate approximately 27 hours a week to student interaction, noticeably more than their counterparts in Scandinavian countries.

Beyond classroom instruction, about 35% of their time involves essential yet behind-the-scenes work such as lesson planning, grading, administrative duties, and communication. Around 15% of a teacher’s responsibilities extend to extracurricular activities, including tasks like lunch duty, coaching sports, and supervising field trips. Reflecting on my own early teaching days, I recall taking on lunch duty — often considered the least desirable role, but it paid an extra $200 each month.

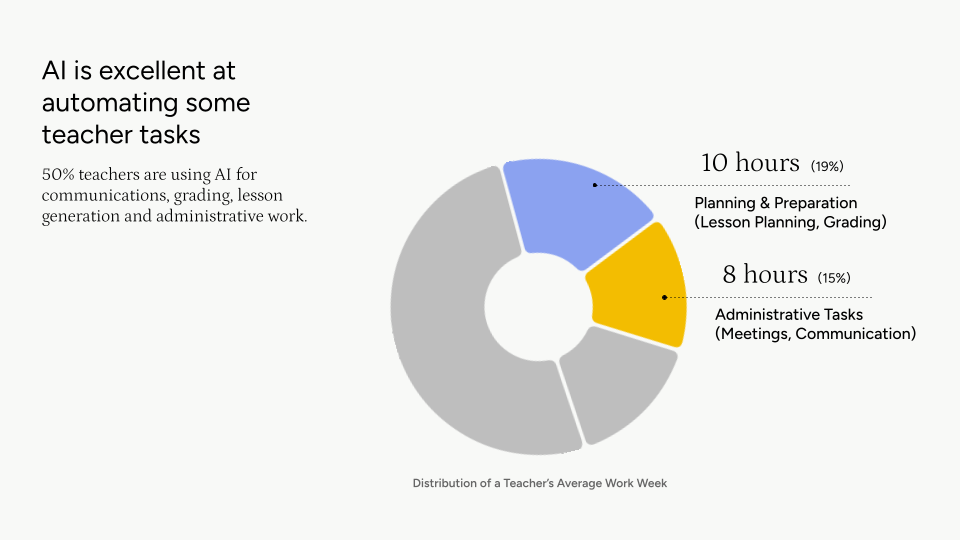

If we look at how AI is reshaping the job of the teacher, it is already excellent at automating tasks in some of these categories – grading, communication, lesson plan generation, finding materials and data reporting. The latest data show that about half of all teachers are using AI for these tasks; it’s reached two million in 2.5 years.

From our portfolio, here are three examples that showcase how AI is helping teachers with planning:

- Curipod, founded in Norway, sees over 600 new teachers come to the platform every day; they are evenly split between Europe and the U.S. The platform is a lesson plan generator with a focus on using AI to develop pedagogically rigorous materials that are aligned to state standards. Teachers spend a lot of time thinking about how to distill content and teach in a way that children will learn best; Curipod simplifies this by generating a rough draft for a lesson that a teacher can then edit and tailor for their own students.

- Songscription showcases something very different. Sometimes the most helpful technologies in education weren’t specifically designed for schools or teachers. Think of this as “Shazam for music transcription”: simply use your phone to record a song you hear (or grab one off YouTube), and then the tech transcribes the song into a score for any instrument. Imagine you are a high school music teacher who needs sheet music tailored specifically to the instruments your orchestra actually has. Currently, finding, downloading, and adapting sheet music is cumbersome. Songscription aims to remove much of that friction.

- Despite its relatively early stage, Teachy has already become the most popular AI tool for teachers in the Global South, and most widely used AI for teachers in the world. Similar to Curipod, it generates lesson plans, but it is specifically designed for non-English classrooms where there isn’t a 1:1 device setup.

The Immutable Science of Human Development

AI is actively changing education, but it’s important to not lose sight of this: As humans, we develop in ways that bind us to each other.

We are social animals and still learn best through human interaction – especially children whose brains are highly attuned toward social learning. AI does not excel at tapping into the biology behind a child’s motivation to learn. AI is not inherently creative. It does not do well with tasks that require complex human judgement. Motivating a 13 year old to persist in their learning and push through frustration requires a very complex set of human skills. These are the skills that we need most in the 27 hours per week that teachers spend with students.

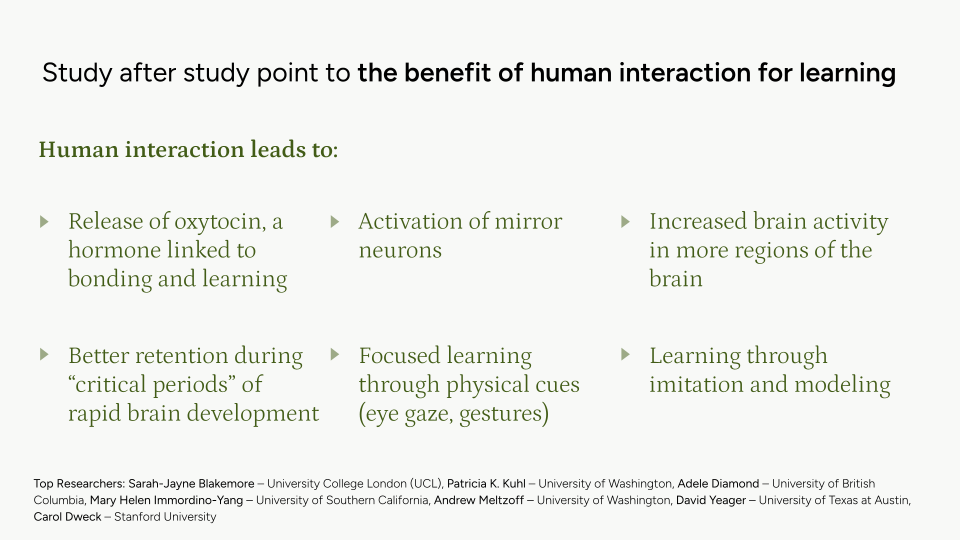

Studies after studies point to the benefit of human interaction in learning. For example, Dr. Patricia Kuhl has done interesting research around how babies acquire language. She compares physical presence to audio and screens. Babies acquire language through human voice; there’s a biological reason why parents speak in “parentese” using exaggerated syllables and higher tones.

We know that the brain of a teenager is highly sensitive to peer approval so they are doing a lot of imitation during this time, primarily activated through mirror neurons. Young children figure out how to direct their attention and how to separate signals from noise by tracking eyes, watching gestures, and listening to voice intonations.

These personal interactions with students is the very reason many teachers, myself included, entered the teaching profession. Helping a child learn has got to be one of the best feelings in the world.

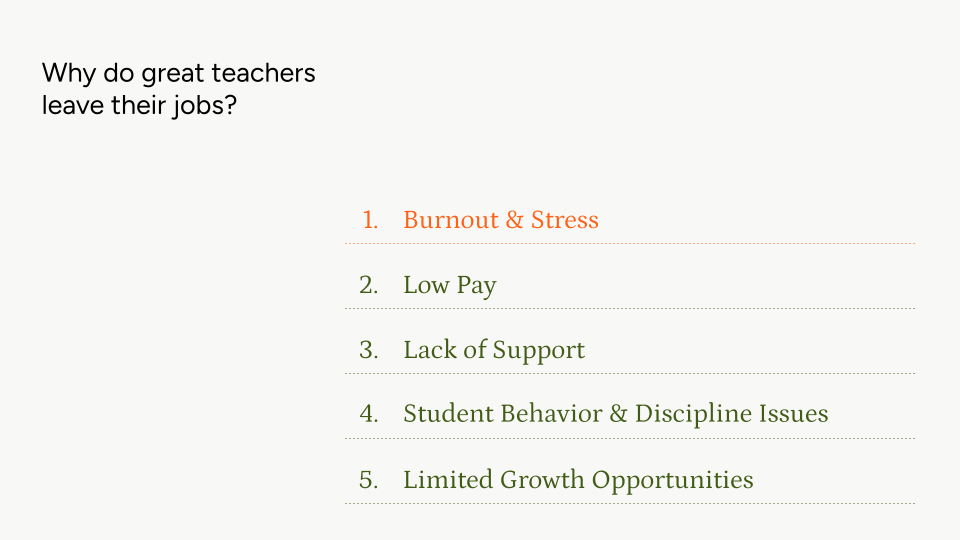

Yet, why are teachers leaving the classroom? Why are fewer and fewer people choosing teaching as their profession?

It’s not lunch duty. The leading cause is burnout and stress.

What if AI afforded teachers more time to create and lead magical, human-centered learning experiences and less time on tasks that cause burnout?

Could we reduce stress and burnout, and bring the joy back to teaching if:

- The job was 40 hours per week instead of 53, cutting workload by about one-third?

- Teachers could off-load most administrative tasks, grading, and reporting?

- They had better tools to craft incredible learning experiences for children?

Let Them Innovate!

I’ll close with a final thought directed particularly toward those who invest in education innovation.

At Reach, we’re always looking for teams that elevate both gifted technologists and child development specialists or education experts. Some of our most impactful products beautifully marry these two skill sets. Building meaningful innovation in education is challenging, especially because many talented technologists are often drawn to more glamorous sectors such as consumer apps, fintech, or gaming.

When you find a gifted technologist who is passionate about building for teachers – back them. Resist the urge to be overly prescriptive with milestones and checkpoints and red tape. Let them innovate, let them build!