Startup Lessons – and Sins – From Former YC President Geoff Ralston

“It’s way better to have ten users who love you, than 1,000 who sort of like you.”

— Paul Buchheit, longtime Y Combinator Partner and creator of Gmail

Y Combinator has dispensed countless timeless advice like this to thousands of founders over the years. Geoff Ralston, who has been with the pre-eminent startup accelerator for over a decade, recently joined us for an AMA fireside chat with the Reach community. The conversation touched on which advice still rings true, what’s changed, and the nuances of building in education. Geoff was also a co-founder of Imagine K12, the first edtech accelerator program for edtech startups — many of which are now in the Reach portfolio.

Below are highlights from that conversation, condensed and edited for clarity.

On what YC startup advice have remained timeless — and what’s changed now.

One of the unspoken truths about YC is that for the most part, the advice we give is incredibly basic and because of that, timeless things like focusing on making something that people actually want will never, ever change. It’s like Jeff Bezos’ saying: “Customers will never not want more selection, faster delivery, cheaper prices.”

Focus on what’s important. Get clarity as to what’s important. Growth matters. Get your product in people’s hands as soon as possible. That’s how you learn and that’s how you start to measure.

There are certainly things that have changed, particularly how you think about developing your software, and how quickly you can launch. With AI, the bar for how quickly you can move is much, much higher. Nowadays a programmer like me can build a product that people can use instantly. If someone comes to an accelerator or investor nowadays and they haven’t built anything at all, that’s shocking.

That said, for any startup advice there are always caveats. Growth is good, but growth at all costs — perhaps not so. You tell founders they should be arrogant in their belief about something, but you can’t be arrogant to the point where you ignore good advice along the way. Which advice is right for you and the moment, and how do you know? As a founder you’re always toeing these difficult lines.

On the importance of “animal” founders.

The best companies hire incredibly well and incredibly slowly in the beginning, and I don’t think that’s ever changed. The competition for talent, especially software engineers, has always been difficult and it’s never been more difficult than it is now.

Basically we say two things. One is “hire slow, fire fast.” And the second is to use your networks: Hire people who are either one or two degrees away from you who you know are great.

Every founder should read Paul Graham’s original essay “How to Start a Startup.” There’s one part that explains why co-founders and early employees should be animals, by which he meant people who aggressively grab on to problems — even ones you don’t see — then just solve them and move on. These people may be edgy and difficult to work with. But you don’t have to push them to act (in fact, if you’re pushing them to get things done, that’s a bad sign).

There are other qualities you want, like complementary talents. People you can get along with, who you can fight with and then hug it out and move on. In the early days of a startup, you’re going to be around these people more than your family, so you have to find a way to still have respect and make it work.

What kills startups more than anything else is founder breakups. The most important aspect of founder relationships is open communication. If you’re holding things in, those issues fester. You have to be able to yell, get it out, then move on to the next thing.

The deadly sin of fake growth.

A common deadly sin is believing you have product-market fit when you don’t. As a founder, you obviously want the customer to use and buy your product. But do they really care about it? If you shut down today, would anyone care?

It’s easy to fall into the trap of fake growth, especially during a bubble, like we had during the pandemic. Often the availability of capital is directly proportional to fake growth. You can buy users because internet advertising has never been easier. But you can’t buy customers who love you. Product-market fit is finding users that love you and will tell you everything that’s wrong with your product — and still can’t stop using it. That’s what you want.

Another mantra we often drilled at YC: It’s way better to have ten users who love you, than 1000 users that sort of like you.

We used to tell our edtech companies: People generally want to be nice — particularly teachers. They’ll say they love a product and it’s great, but when you come right down to it, will they actually use it? When push comes to shove, they might say “I don’t have time or I’m too busy.”

Talking to users and getting useful information and feedback is an art, and not a science. You have to get a sense for whether the product matters to users, and this doesn’t just come from asking yes or no questions.

On good indicators of product-market fit.

I have two favorite definitions of product-market fit. The first one is from Ooshma Garg, founder of Gobble, who said product-market fit lives at the intersection of growth and retention. If you’re in a situation where your customers fundamentally don’t churn and your growth continues to ratchet up, that’s a good sign.

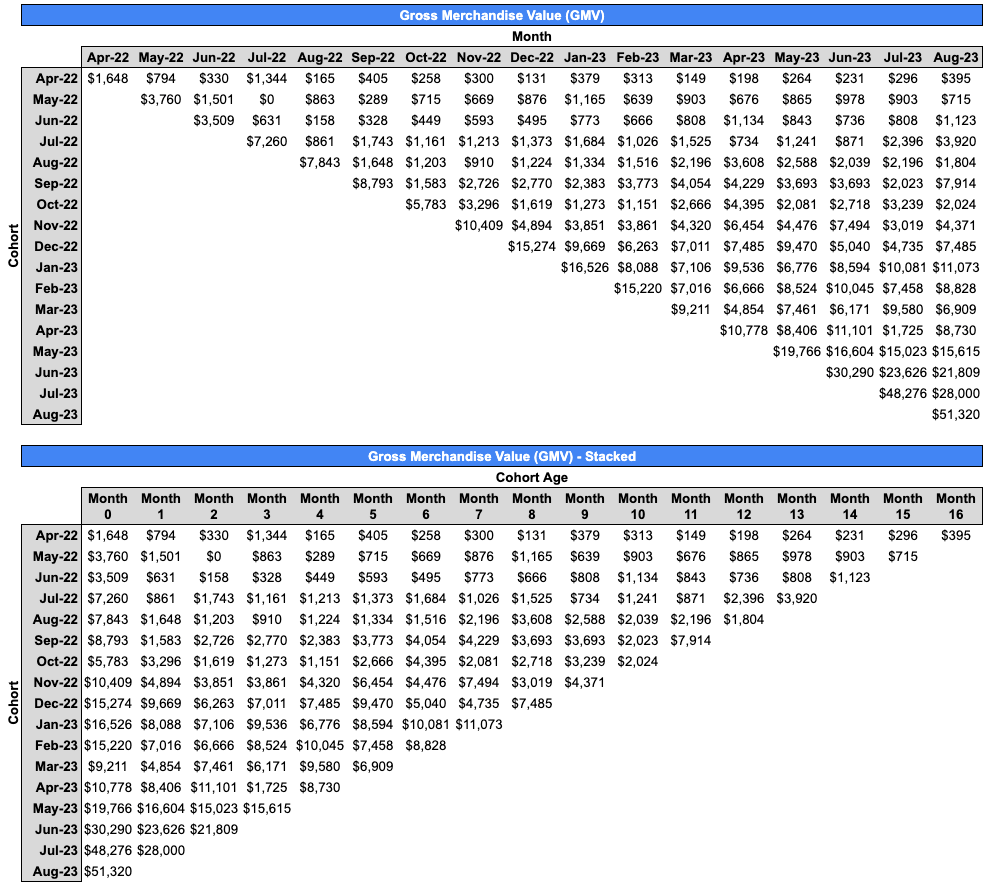

Real growth is the best indicator of product-market fit, and that you’ve built something that people want. I think it’s the best indicator of future success (although not the only one). So it’s important to look at cohort-based churn numbers. If the numbers aren’t pretty, then you probably don’t have product-market fit yet — and persuading yourself that you do is very counterproductive.

My other favorite definition comes from Emmett Shear, the founder of Twitch. He likened product-market fit to the Greek myth of Sisyphus, where he was pushing the boulder up the hill and it kept on rolling back on him. If you feel like you’re pushing the ball up the hill and then it keeps on rolling over you, that’s not quite it. But if you get to the top of the hill, and suddenly you’re running after the boulder because it’s rolling too fast, then you’re much more likely to have it.

On the dangers of magical thinking.

There’s this fundamental thing that founders do — they think magically, which means they imagine things to be true when they’re not. We’ve talked about product-market fit. Another common one is believing someone is going to work out when they’re not. You’ve hired the wrong person, and you persuade yourself it’s going to be okay.

Also, the things that you don’t like doing are often ones that are most important for the company. The canonical example is startups founded by engineers. Someone needs to be selling, but it’s way easier and more comfortable to be typing. Learning how to be the right storyteller to customers is super important, and it’s easy to ignore that. This is another classic failure mode, because if you’re not getting customers to use your product, you’re not learning and you’re not iterating to get to the point where you have a successful company.

On navigating the challenge in edtech when your users are not always the buyers.

It’s always a challenge when your customer isn’t the one with the wallet, and in edtech there is an extra layer of difficulty in pursuing a double love affair — you want both kids and parents to like you. If the kids love you and the parents don’t, then it doesn’t matter how much the kids keep on using the product; you’re unlikely to build a sustainable business.

The key thing here is understanding where and how the buying decision is made. The buying decision might actually still be with the kid, and they might have a credit card from their parents. You have to understand that and have great clarity as to where that buying decision is made and how you incentivize that buying decision, whether it’s the kid or the parent.

Another challenge with edtech is you have sort of this built-in churn in the summer, when everyone stops using your product. The real question is: What happens in the fall? Who comes back? That can be super nerve wracking.

Credit and thank you to Jennifer Carolan for facilitating this conversation.