This post was originally published in the Grounded newsletter.

Author’s note: We know this is a lengthy article. Given how meaty this topic is, we believe the extensive background and context are important. We encourage you to read through all of it if you’re interested in learning about: 1) our hypothesis on why young people today are in a state of identity crisis or, as we call it, “identity moratorium”, 2) five key trends that drive this crisis, and 3) characteristics we believe new online spaces for young people should embody to better support healthy adolescent identity development. With that, please read on!

The title of this article isn’t entirely right and probably a bit misleading, but it was one of the more provocative ways Maria started our weekly ramen dinners (and, if you know her, you know this says a lot). In the metaverse and NFT craze of 2021/2022, we became obsessed with avatars and their implications for identity. In typical Grounded fashion, we spent many weekends, nights, and meals discussing research on the history of digital and analog representations of self, the impact digital profiles have on identity, how adolescents develop identity, and more. During one of these deep dives, a light bulb went off when we started talking about the historical relevance of Barbie.

First, let’s start with a little background. One of the first times the term “avatar” entered the computer gaming vernacular was with the launch of the popular role-playing game (RPG) Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar. From 1982 to 1999, Ultima released nine installments, but, according to the PC Gamer’s the history of PC RPGs, “Ultima was simply another popular RPG until Ultima IV.”

The first three games focused on defeating an evil and immortal wizard. Richard Garriott, the creator of Ultima, felt this was an opportunity for players to role-play being “heroic”. As it turns out, the opposite was true. Most of the fan mail repeated similar stories of enjoying killing all the non-player characters (NPCs) and stealing. Garriott said, “I realized they weren’t being heroic at all.. that’s when I adopted the word ‘avatar’ from a religious context.”

Avatar is a Sanskrit word defined as a deity’s reincarnation in human form. Unlike other RPGs at the time, the player in Ultima IV was not a fantasy character. To Richard, it was “important that it felt like your soul, your spirit, be inside your character so that you feel responsible for the deeds and actions your character performs.” This sentiment inspired a unique element of the game – a “gypsy” would greet the player and ask a series of ethical questions about eight virtues: honesty, valor, compassion, justice, spirituality, humility, sacrifice, and honor. Player’s answers determined the character they received or their “avatar.”

We will talk more about Ultima IV and how its intentional game design helped users explore their own identity later on, but, with this context of an avatar in mind – let’s turn back to Barbie and why Maria said she was the first avatar for young girls.

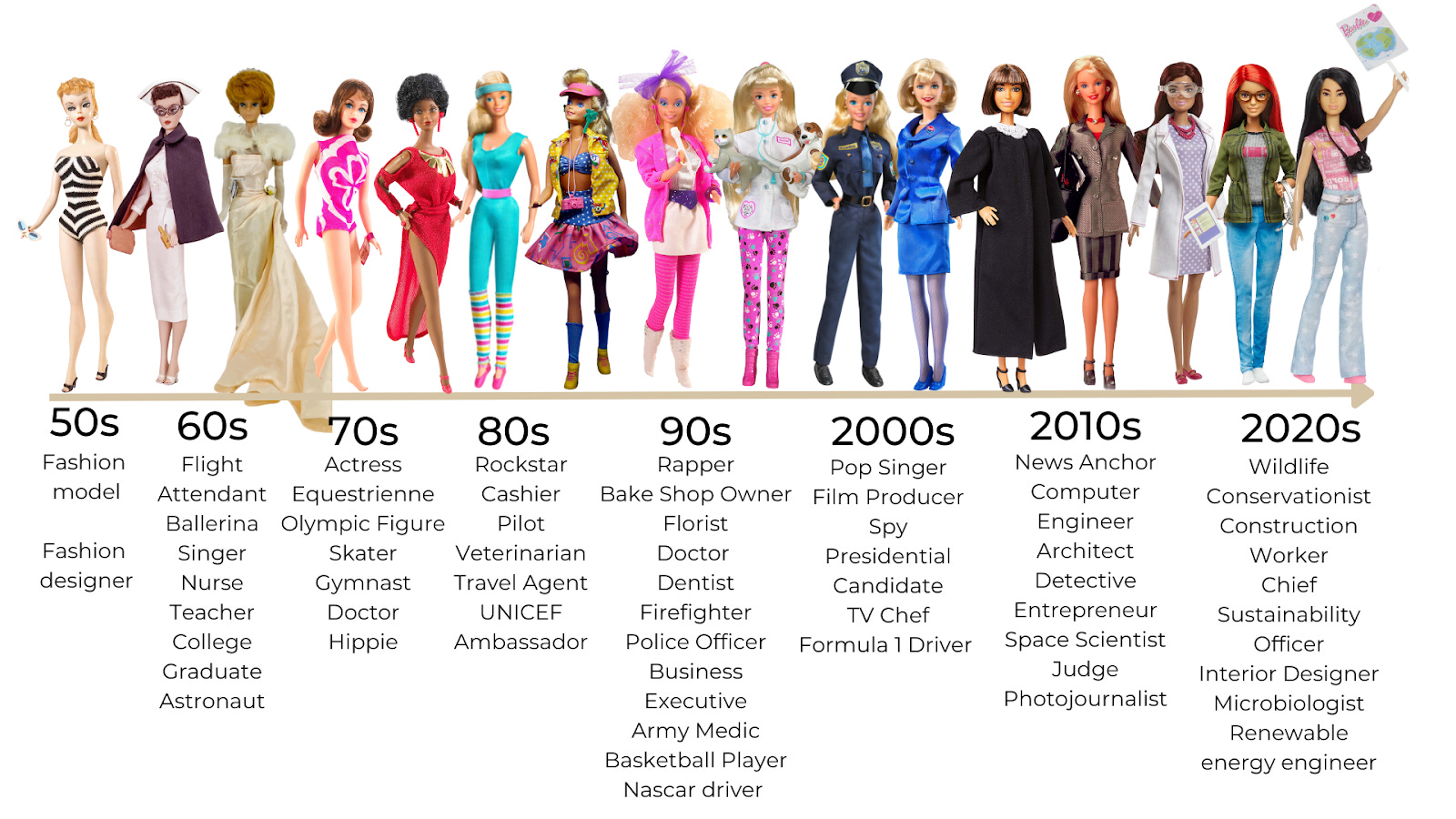

Before Barbie, young girls often played with 2D paper-cut dolls they could customize (see below). But, in 1959, Mattel’s founder Ruth Handler teamed up with a space engineer to develop a single 3D character toy named Barbie. Commenting on Barbie’s purpose, Handler said “My whole philosophy of Barbie was that, through the doll, the girl could be anything she wanted to be…Barbie always represented the fact that a woman has choices.” Since her initial launch, Barbie has lived many lives — largely driven by the culture of the time.

In the 50’s, she was a fashion model mirroring the style of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor. In the 60’s, she took after Jackie Kennedy – with only slightly more career choices (ballerina, fashion designer, babysitter, teacher, flight attendant, nurse etc.). This trend carries on with each passing decade. Fast forward to the 2020s and Barbie’s wardrobe and skill set continues to expand – with careers ranging from zookeeper and construction worker to entrepreneur, detective, and more. 60 years later, the world Handler envisioned in which any little girl could see Barbie and see herself has come to fruition — at least, in theory.

But that wasn’t entirely true. It was at this point in the dinner the lactose-intolerant Maria took a large gulp of her thai milk tea and a bite of her burrata, while Jomayra shed a tear from her way too spicy ramen. We both knew the idea of choice when it came to Barbie was an illusion. Barbie’s careers and identities aren’t limitless. They’re developed in a top-down and one-directional process led by a slow-adapting company that, let’s be honest, can be straight up offensive. While this is not much of an epiphany, our discussion took an insightful turn as we started unpacking how complex determining your identity becomes when your option set is infinite and bi-directional.

And that brings us to the crux of this article: What does it mean to develop your identity today?

Maria jokingly likes to ask, “When I can be a literal noodle in a game, how can that be good for identity development?” Disregarding the bizarre example, her question has merit.

When your aspirations were solely influenced by toys, families, friends, media, and analog experiences, your identity development felt pretty limited compared to the reality for young people today. Avatars and digital worlds are obviously not new, people like Richard Garriot have been dreaming of them for decades – but the pervasiveness of it is. Today, these digital worlds live in the hands of hundreds of millions of users across the world, many under the age of 18. In these worlds, young people build their own online identities – not limited to a fixed set of characteristics like boy, girl, white, black, etc. Instead, they represent themselves however they’d like and change as many times as they’d like – or at least until their Robux or digital currency runs out.

Then, they explore these identities by role-playing different milestone experiences that previously would’ve happened in the real world. Seriously. A study by Razorfish and VICE Media group found that Gen Z gamers spend twice as much time hanging out with friends in the metaverse than they do in real life, with gamers spending 12.2 hours per week playing video games versus 6.6 hours hanging out with friends in-person.

At first glance, this sounds amazing. A young person can try on different identities and experience them in semi-infinite social online situations. And indeed, more than half of Gen Zers surveyed indicated they feel freer to express themselves in games than they do in real life – and 45% reported their in-game identity is a truer expression of who they really are. For those nervous to try an identity in real life, a digital world can be a much safer space to do so anonymously, if needed. For example, a study showed that sexual minority adolescents felt more comfortable expressing their sexuality to others in online contexts.

Given this reality, we presumed that young people should feel more supported than ever to explore and understand their own identities. That said, we suspect quite the opposite is turning out to be true. A world of infinite possibilities has ushered in an era that is not defined by identity exploration, but more of an identity crisis.

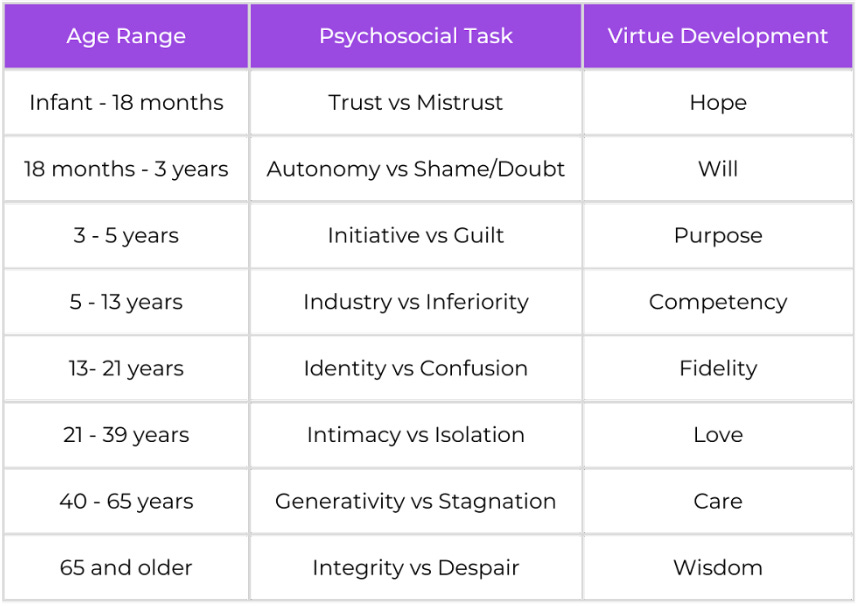

To understand this, we went back to the basics. In the 1950’s, psychologist Erik Erkison introduced his theory on the stages of psychosocial development. He contends there are 8 development stages that can be split up by age range. For example, from birth until 18 months, a child’s primary psychosocial crisis is one of trust. If an infant is cared for by a loving and reliable guardian, they will likely develop a sense of trust that will extend to other relationships. On the other hand, if they do not receive this care, they are more likely to develop a sense of mistrust and anxiety.

Our interest centers on the 13-21 year old stage of psychosocial development – the ages when children start to grapple with questions about their identity and future. It also happens to be the age where children start to increasingly engage in unstructured device time, multi-player gaming, and social media.

During this period, an adolescent explores what roles they want to take on as an adult. They begin to form their own identity and achieve what Erikson describes as “fidelity” or committing to one’s self on the basis of accepting others, even when there may be ideological differences. Across diverse ethnic groups and for both males and females, data show that resistance to peer influences increases linearly from 14 to 18 years of age. So, the mid-adolescence range is an important phase in which young people learn to hold true to their values and beliefs in the face of peer pressure (clearly VCs missed this phase). Over time, Erikson argues they integrate those values and beliefs with social expectations and standards. This integration of self and societal values is the basis of adolescent identity formation. If children “fail” in this stage, the result is “role confusion” or the adolescent being confused about their place in society. Role confusion is linked to increased anxiety, depression, and even suicidal tendencies in adolescents – whereas achieved identity is associated with psychological well-being, emotional adjustment, and greater emotional stability.

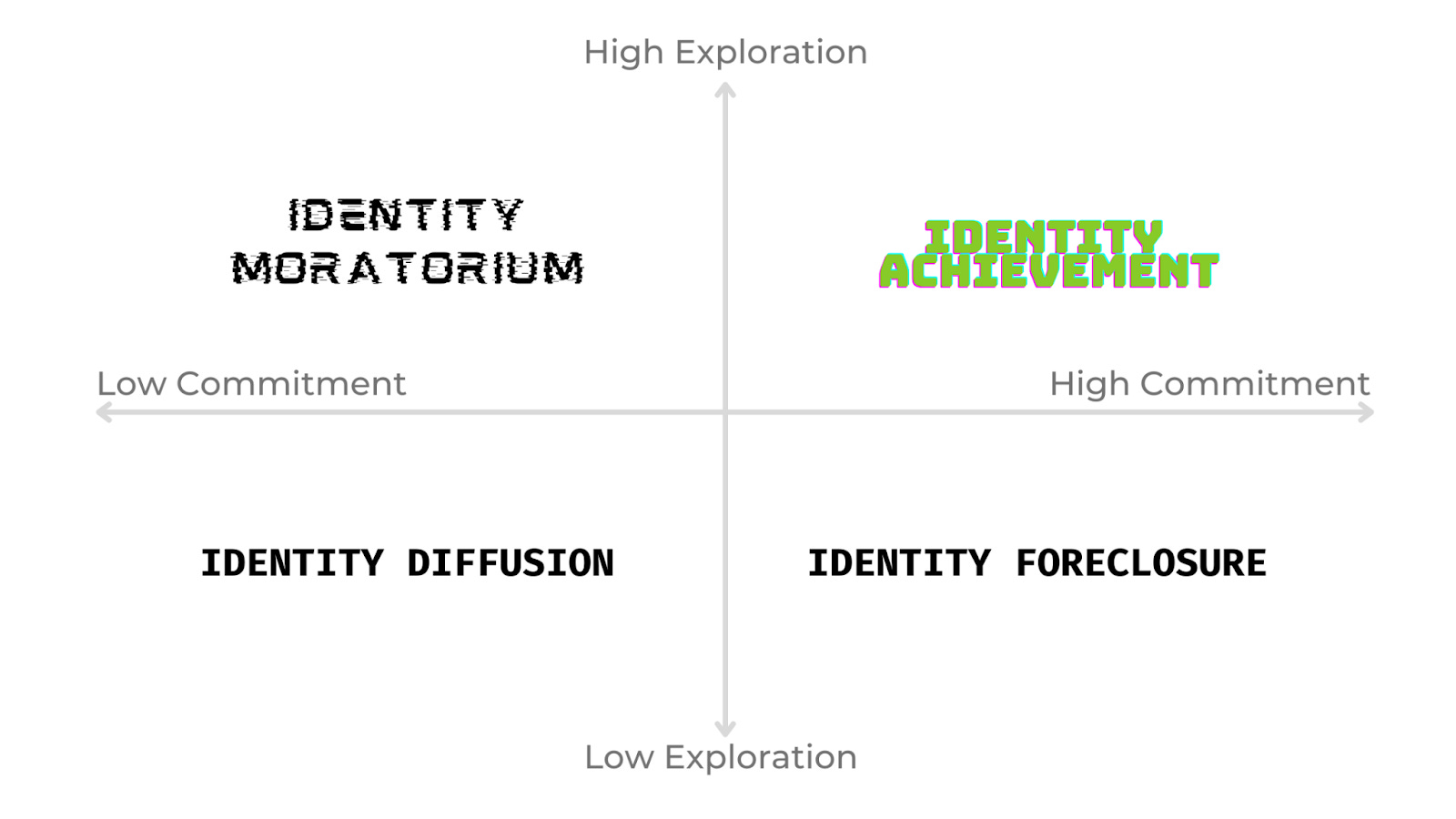

Psychologist James Marcia builds on Erikson’s theory and states that the identity development process is less binary than achievement or confusion. Instead, he introduces four statuses of the process:

- Identity diffusion: When a person has not explored or made identity commitments.

- Identity foreclosure: When someone commits to an identity but has not explored other options. This is often due to pressure from parents, friends, and/or community.

- Identity moratorium: This is a period of active exploration where an individual tries new identities on.

- Identity achievement: When someone has explored different options and makes a commitment.

So why are we talking so much about psychosocial development? Going back to the beginning of our discussion, if we believe that young people have infinite possibilities, we hypothesize that a significant number of them stall in the “identity moratorium” stage as a direct result. They continue to try on new identities and explore, but never feel forced to commit.

Why do we believe this? There are five key trends unique to young people today that drive this trend:

- Identity is easier to explore than ever before: As previously stated, this ease and freedom can be a good thing. For some adolescents, video games and social media allow them to escape from a constraining or judgmental reality in their home and/or school lives. They can try on and experiment with roles that feel good to them. Theories of online disinhibition indicate that individuals are more likely to freely express their opinions and engage in disinhibited behavior online than offline. The challenge with online identity reconstruction is that if adolescents fail to create coherence between their online and offline selves, they are more likely to have negative psychological outcomes, correlating with anxiety, depression, and stress. And indeed, players who create game characters that are inconsistent with their real identity are likely to feel lonely. And the ability to experiment with different identities will only accelerate with the rise of generative AI (you didn’t think we would get through this article without mentioning it at least once), as generating content and assets becomes easier than ever before.

- Immediate and frequent feedback on identity means little time for reflection: In an analog world, feedback is relatively slow, but it’s often contextualized in a deeper, supportive relationship. Now, simply upload a picture, video, or tweet and feedback comes at a rapid pace in the form of likes, shares, retweets, comments, and more. So, while the pace of feedback has rapidly increased, the processing power of young, developing brains has not. In the context of identity exploration and development, this is the equivalent of a data overload – young people find themselves in a constant reactionary state. Noted Gen Z decoder and VP of Insights at Vice Media, Amy Davies writes, “Youth are operating in a kind of identity beta, iterating their way through life in a quest for digital dopamine hits. Youth can begin to lose the agency of assembling their identity, and instead may become more reactionary to the feedback around them.” Research in the Journal of Adolescence on over 4K teens found that without an opportunity for self-reflection, the range of values and norms presented on digital platforms may actually undermine agency goals by making commitment to personal values challenging. An abundance of choice and feedback may actually lead to “ruminative exploration.”

- Identity feels more tied to a “brand” than self: The advent of social media transformed the semiprivate – what you’re doing, saying, where you are, etc. – into a public exhibition. Who you were, how you acted, and how you dressed in-person largely drove how others saw you. Now, young people purposely curate their self image online to showcase how they want to be viewed by the world. The challenge here is that social incentives are warped -young people lean towards posturing and creating an identity suitable for a broad swath of people instead of actually grappling with their real identity. Often the very things that make you who you are may be unappealing to certain groups of people and that is ok, but when you seek approval from hundreds – even thousands! of people instead of your much closer circle, you fall into the trap of building an acceptable brand instead of a true-to-you identity.

- Digital lives are permanent: In an analog world, adolescents historically experiment in potentially embarrassing ways, but, with a limited audience of friends and family, the impact would be fairly constrained. For example, many born before Myspace had their own version of a cringe-worthy emo teenage angsty phase, but there’s no evidence on TikTok or Instagram to be replayed, saved, and shared in perpetuity. Young people were able to comfortably outgrow those experiences in ways that today’s youth can’t. In fact, healthy development requires that narrative identities maintain malleability and that individuals have agency to change them. So, while young people can experiment more today than ever before, the permanence contradicts what young people need for healthy development.

- Digital identity is fragmented: Erikson introduced a concept called a “temporally coherent narrative,” which is defined as a “causally connected, temporally meaningful story of the evolution of self.” This process has long been considered a basic psychological need because it requires a person to incorporate their personal values and beliefs with a diverse range of relationships and social roles in order to build a unified story of self. Multiple studies show that high levels of temporal narrative coherence are linked to improvements in mental health. On the much darker flipside, a lack of it is linked to higher rates of suicide. Researchers from the Behavioural Science Institute suggest that the digital world greatly impacts young people by threatening their coherence process through the fragmentation of different platforms. They write, “There is a massive number of digital spaces in which young people act and interact and individuals’ experiences with the array of digital spaces may result in feelings of self-fragmentation and a lack of temporal narrative coherence… [Young people] have likely left a variety of identity-relevant texts, photos, videos, and other forms of self-artifacts across a range of digital spaces from around mid-adolescence until early adulthood. However, there is currently no way to synthesize, order, collect, or edit these various self-artifacts across the digital ecosystem.”

So– why do we, the VCs, care about this? Identity is at the core of everything we do. It drives how we spend our time, what job we choose, how we like to express ourselves, who we fall in love with, and more. As Erik Erikson said, “In the social jungle of human existence, there is no feeling of being alive without a sense of identity.” And yet, we see the identity exploration and achievement process weaken for entire generations right in front of us and we’ll continue to experience the impact of it with drastic spikes in mental health challenges. Instead of focusing on reactive solutions, we’ve become obsessed with thinking about what it means to just build a stronger foundation that young people can grow from.

We know the answer isn’t purely technology-based. In fact, young people need to go back to spending more time outside, unsupervised, and with their friends. It’s no wonder the phrase “go outside and touch some grass” has become popular on TikTok and Twitter, as young people acknowledge what they lack with a bit of humor. But, we remain aware that the amount of time young people spend online isn’t realistically going to change en masse. So how do we create a place (or places) that feels fun and novel, but is built on principles that are actually good for youth development?

We have no idea what this platform will look like or if it’s necessarily only one product – that’s why we’re the VCs and not the founders. But here are some characteristics we think it will contain:

- Intentional connection with digital self: Let’s turn back to the game we briefly introduced at the beginning of this article, Ultima IV, as it provides a great example of intentional design that bridges an offline and digital self. If you recall, each player receives a personalized “avatar” defined by the player’s answer to the series of ethical questions related to the eight virtues. Then, game developer Garriot created a back-end karma system in which his non-player characters (NPCs) would forgive, but never forget if they were treated poorly by potentially withholding assistance later in the player’s journey. To complete the game, players embarked on the quest to become a better person. While there were monsters and dungeons, there were no villains. Winning meant embodying the eight virtues to become the Avatar of Virtue. The concept of the avatar allowed Garriott to create a completely new player experience. In the game, players grappled with tough decisions that directly related to the eight virtues. They couldn’t disassociate from the player as, in a lot of ways, it represented core parts of themselves. As a 1999 reviewer of the series said, “[Ultima has] been firmly grounded in a world where a character’s virtues are as important as their armor class in determining success.” We think that Ultima IV illustrates how intentional design inspires a true connection between the offline and online self. This stands in stark contrast to companies like Roblox or other games where users can create avatars that may have no connection to who they are in real life.

- Discomfort as feature: According to Erikson, identity development depends on “person-society integration” processes. When a young person struggles with the dissonance between their own values and their community’s values. In a bubble of safety-ism, which has come to define Gen Z’s upbringing, many did not have their views challenged and, as a result, did not have to go through the process of recommitting to them. It’s no wonder they flow between different identities with ease. Creating a sense of mild discomfort by forcing young people to grapple with their own views should be treated as a virtue. Nassim Taleb’s theory on anti-fragility engages this topic – thriving ecosystems and organizations gain from chaos and stress instead of crumbling. The same idea applies to the social and emotional systems of young people: within reason, stressing them actually makes them stronger.

- Active vs passive engagement: We can endlessly debate the benefits of social media, but one thing we know is that overall impacts fluctuate in intensity based on the way users engage. Research indicates that passive engagement leads to social comparison and envy, whereas active engagement creates social capital and increased feelings of social connectedness. This is an area where gaming has a leg up, as players are actively engaged and participating – not simply passive consumers of information. The more active a user is, the more they are aligned with their own agency and portrayal

- A unified experience (or the metaverse, if you want an obligatory cliche): Say what you want about the metaverse, but there is something appealing about a unified ecosystem where identity flows easily between digital spaces. As stated previously, young people struggle to develop a sense of identity coherence when they play different roles and develop separate identities on each platform. With a more unified ecosystem, the next generation can traverse across the digital world with a streamlined representation – laying the foundation for a stronger sense of coherence.

- Less performative, more intimate: Social media is performative. Young people develop their “brand” and it lives on the internet semi-forever – effectively setting their identity in stone. That said, there are interesting ways to make experiences more intimate. For example, when Instagram launched Stories, their 24-hour ephemeral feature, it significantly increased private one-to-one messaging between users. While not a perfect example, as Stories certainly still feels performative, it indicates that there are ways to encourage healthier behaviors among young people on existing platforms. Journey, the fastest-selling video game of 2013, provides another compelling example of creating an intimate, purposeful video game experience. Journey is a nonviolent, social video game that encourages cooperative, non-verbal play. In the game, users helped care for each other, rather than compete. Players often indicated how the game inspired them to think differently about their own relationships outside the game. Vanity is a deadly, hard-to-avoid sin, but online spaces can still provide young people with enjoyable experience that avoids the performative nature of social media today.

- Fun, different, and special: As an ed tech investor, Jomayra has heard the vision of “Roblox for Learning” a million times. Here’s the truth: kids want to spend their time where it’s fun. They don’t want the brussel sprouts with the bacon; they really just want the bacon. A winner in this space leads with fun and, if built correctly, benefits the child. This might not be evident in their test scores — at least, not at first. But, you’ll see strides in their communication, the strength of their friendships, and their happiness. And that’s a good thing.

- Space for reflection: Young people receive more information and feedback than ever before. And their identities exist in a large range of digital spaces, which may or may not even translate to their offline lives. It’s a lot. In fact, it’s too much for an adolescent to process. They need time and space to reflect. Future platforms and/or features should incentivize solitary self-reflection in order to help young people digest and reconcile everything that comes their way. Companies like BeReal and Dispo have incorporated some of this realization into their products by limiting the time users spend in the product to a certain time of day and encouraging them to spend more time in the real world.

The world for young people has changed dramatically, but how they internally process it hasn’t. If we care about the alarming mental health challenges we observe today, we posit that our response must center on protecting young people’s precious identity development by influencing the way they spend time online. Barbie won’t save the kids, but we can. If you think you’re building this, ping us at jomayra@reachcapital.com and maria@uluventures.com.

A heartfelt thank you to Ellen Schneider, Meera Clark, Alex Marshall, and Jennifer Carolan who all took the time to review and edit this before we published it!