by Esteban Sosnik

Dear Esteban,

I started an edtech company a couple years ago. We had a great idea, we did an accelerator, but we never got any amazing metrics. I still see a lot of potential, but do you think we could raise money from a VC? What do you really look for in an edtech entrepreneur?

— Metrics Anxiety

Dear Metrics Anxiety,

The general conception is that you can only raise money from a VC when you have amazing metrics. However, metrics are relative to where you are in your company trajectory.

There are two things I look for in an edtech entrepreneur when I’m evaluating an investment. The first is your relative “efficiency and velocity” — how much have you accomplished with the resources you’ve used so far? The second is your “learning” — how well have you leveraged your mistakes and the user behavior you’ve observed (your data) into a deeper understanding of your market, your user, and your product?

Efficiency and Velocity

A Ferrari can travel 100 miles very quickly, but it burns through a lot of gasoline in the process. Meanwhile, a Vespa can travel 100 miles using very little fuel, but it’ll take you a much longer. So, velocity = distance / time and efficiency = distance / cost , and I’m interested in both. That is, given the time and money you had, how far did you travel?

As an early stage investor, I don’t focus on how far along you are with your product; instead, I really dig in to determine how far you’ve gotten relative to how much time and money you had to work with. This may sound obvious, but it is often overlooked. (Of course, which metrics best represent your progress is also essential, and I’ll address that in other posts.)

Learning

The second thing I look for is how much you’ve learned along the way. Are you listening to your customers? Why do your users love you, and how are you making them love you more? Are you responding to their needs effectively? Learning is often about how you leverage mistakes or false starts. Maybe you tried something early on in your business that didn’t work out — how did that shape your future decisions for the better? Have you become a better entrepreneur because of it? In what way?

When you’re pitching your company, you should never hide your mistakes or what you’ve done wrong. Tell us what happened and what you learned from it, and what you’re doing now that you’ve learned this valuable lesson.

Let me give you some examples in edtech.

Efficiency and Velocity: the Mathpix Case Study

Mathpix, founded by Nico Jimenez, is an app that uses handwriting recognition to solve a wide variety of math problems, providing step-by-step solutions and interactive graphs. When I first heard Nico’s pitch, he was pre-launch but had bootstrapped an MVP and built the backend machine learning technology that I saw as a big competitive differentiator. He had been working on this tech in his spare time for more than a year, but, importantly, he had spent no money on the app and had developed a technology that is world class. That’s amazing efficiency, and helped compel me to invest in his company.

Fast forward to today, about a year later, and Mathpix has traveled a long way. They launched their app. They have more than 400,000 downloads (more than 20% of which are active). And they are generating revenue via their APIs with several partners integrating their backend technology. This is an example of excellent velocity.

Great efficiency and/or great velocity sends a strong signal, and Nico is an example of an entrepreneur who has impressed me with his efficiency velocity.

Learning: the BetterLesson Case Study

BetterLesson, founded by Alex Grodd and Erin Osborn, started off as a content marketplace trying to aggregate and share better lesson plans for teachers. After growing the marketplace, however, they were not satisfied with their ability to curate the quality of the lessons — similar to most user-generated marketplaces, the uncurated content simply produced too much noise. Open-eyed about the varied quality filling their platform, they pursued a new strategy. They landed some grant funding to pay master educators to create excellent lessons that teachers would be proud to use in their classrooms.

Even with these “better lessons,” the company still struggled to dramatically improve teacher practice. They recognized that the lessons were only the first step. The team discovered that teachers often needed to adopt new pedagogical practices in order to execute these lessons effectively, and there were many teachers that lacked the support to make this transition. Using this insight, BetterLesson pivoted again, and began offering professional development (PD) programs with virtual coaches. Now teachers work with BetterLesson coaches to set objectives and key results for their teaching practice, and use the platform to make progress toward these outcomes. And, BetterLesson is documenting these teachers’ professional development process, and using that material to create a scalable version of their PD methodology.

This is an example of a great entrepreneurial team with extremely high “learning.” They’re on their third life and still running. They’ve zigged from VC funding into grants, and have now zagged back to VCs with a $6M round in October 2015. In their 8 years since founding, they may not have built a billion-dollar business (yet!), but they’ve learned , and they’ve applied their learnings to great effect. Their business is now in a great place, generating significant revenue and poised for growth.

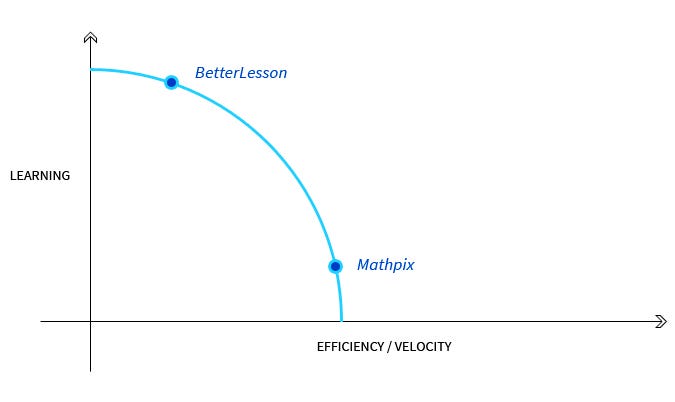

This chart shows how there is often a tradeoff between the two things I look for in an entrepreneur. A company that has been hyper-efficient with resources and extremely quick to market probably didn’t need to suffer through many tough lessons and maybe hasn’t gained a lot of hard-earned wisdom. On the other hand, a company that has learned a lot about its users — through many iterations of product prototypes and some trial and error — probably used a little more time and/or cash. In my work at Reach, I like entrepreneurs who are on the “efficient frontier,” like Mathpix and BetterLesson.

In short, don’t worry about guessing what metric will catch the attention of an investor. The story of how you got where you are is what makes you unique and provides context for your work. As an investor, hearing that story is what I value the most.