Dear Guido,

My co-founders and I have spent the past six months developing a software application for K-12 classrooms. We have received pretty good early feedback from teachers and students and think we have a reasonable pricing model. But I know nothing about sales, and even less about how sales work in the education system. To get my product into schools, when should I hire my first salesperson? Have I already waited too long?

— Birth of a Salesman

Dear Birth of a Salesman,

You shouldn’t hire your first salesperson until you know you have a product that sells. That means that as the founder of a product, you are your first salesperson. In fact, if you’re not selling your product from day one, you’re missing out on valuable learning opportunities.

Why are sales so important? Because selling is one of the best ways to start learning about your product.

As three immigrant founders with very thick accents and zero experience in the K-12 system, we were nervous to start selling Nearpod. We called little schools, big schools, private schools, public schools — just about any school that we could get a hold of — and eventually we sold our first account. But even when we didn’t make a sale, we discovered so much through our conversations with customers:

“It would be neat if you did this…”

“I’ll have to call you back in July when I have my 2012 budget…”

“I don’t understand how to get to this feature…”

“I love it! But as a principal, I can only spend [$x,xxx] on a product. Anything above that goes to the district.”

“Oh, this is just like [some other product].”

Using the feedback from our early deals, both won and lost, we revisited our landing page, our signup flow, our pricing model, our sales strategy, and our marketing plan.

My biggest learning in these initial sales calls was around how to price our product. From principals, I would hear things like: “If my teachers are asking for something below $2–3K, it’s a no-brainer. I can buy it.” You simply cannot outsource an insight like that. Even the smartest salesperson doesn’t usually convert this type of dialog about a principal’s discretionary budget into an insight about pricing for your company. With salespeople, the incentives are different — they’re thinking about hitting quotas and the binary outcome of the sale. Early on, you have to be the sales team.

Then, when you start gaining traction and have closed a stable set of accounts (for us it was around 10–20), you’re ready to hire an official salesperson! More on what to look for in a salesperson in a later post.

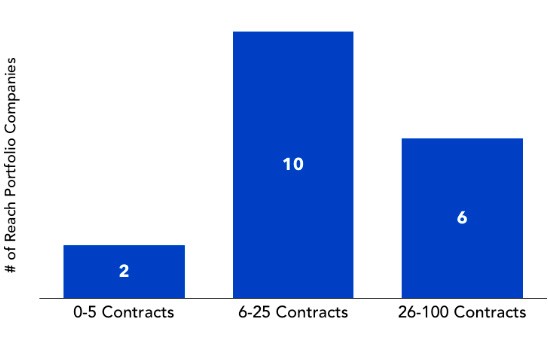

(A note from Esteban: We asked 18 companies from the Reach portfolio, “How many contracts did you sell before you hired your first salesperson?” The results from this informal survey support what Guido suggests: The average was around 28 paid accounts, with only a couple under 5 and no one over 100.

John Danner, Co-Founder and CEO of Zeal, says they moved a current employee into sales at about 5 customers and hired their first full-time salesperson at 20 customers.

“We also experimented outsourcing for a quarter,” he noted, “which was a terrible mistake.” Greg Bybee, VP of Marketing at NovoEd, agrees with Danner, adding that it is “critical that 100% of the learning from the field comes back to the company to impact the product.”

While this is not a formal study, it illuminates how founders of early stage startups spend significant time selling their product before bringing in a sales team.)

Early on, it is crucial that you don’t make a distinction between founders and salespeople. If you are a founder that can’t sell, find a co-founder who can. Between fundraising, hiring early employees, gaining adoption in schools and districts, and developing partnerships, you need to know how to effectively sell your idea to everyone you encounter.

So, get working on your elevator pitch!