by Jennifer Carolan

2015 was a big year for personalized learning. Nearly every edtech pitch I saw opened with a black and white image of a 1950’s one-size-fits-all classroom, and proceeded to tell the story of how startup X would fix schools through personalization. In a world where we expect our Starbucks drink customized, gifts recommended by Amazon and music playlists tailored to our taste, why should education be any different? Personalization seems like such a natural target for the educational pendulum to swing to after years of factory model schooling.

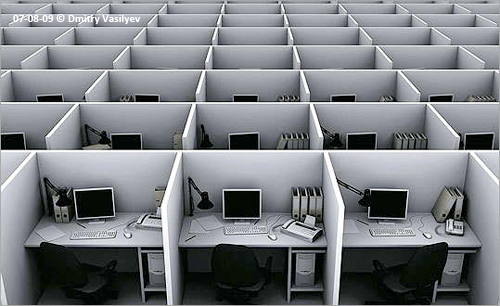

With all of the investment hype and entrepreneurial frenzy, I worry that some might view personalization as yet another silver bullet for education. Or worse, if we mistake personalization as an end-state and combine it with the (over)promise of adaptive technology, than we risk our classrooms going from the old fashioned factory model to this:

This image may be extreme, but we see similar things all around us like families out to dinner with faces in their phones rather than looking at each other. I too struggle to find quality, tech-free family time. Technology is immersive, all the more so when personalized. However, when applied thoughtfully, it is a powerful strategy for connection, integration and growth. In fact, the impetus behind the personalization movement was inclusion, not isolation. Let me explain with a brief history.

Despite claims to the contrary, the shift from one-size-fits-all to a more personalized approach to learning began with teachers, not techies. Personalization has its roots in the special needs classroom where educators had to get creative and innovate beyond traditional teaching methods in order to teach unconventional learners. Some of these students had learning disabilities like dyslexia or dyscalculia, while others were advanced and bored by content learned years earlier. These extreme cases demanded new, personalized teaching strategies and were then often codified into a child’s IEP or Individualized Education Plan. Soon Differentiation became “a thing” and it was further popularized in the 1990’s by UVA researcher Carol Tomlinson. It’s popularity amongst educators really took off as various court rulings throughout the ‘90’s fleshed out a core principle of IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) called “Least Restrictive Environment” (or LRE in edu-jargon). Put simply, LRE states that schools must make every possible effort to integrate special needs students into the mainstream classroom. What happened next was very exciting — with the inclusion of these students into the regular ed classroom, came their innovative and personalized strategies, breaking the calcified mold of the one-size-fits-all classroom. As it turned out, these strategies proved promising for all students by enabling more access points for learning, and so began the shift toward greater personalization.

To this day, differentiation is the most requested topic of interest by teachers for professional development according to ASCD, the nation’s largest professional development provider. Great teachers know that instruction designed around the individual ought not be isolating but engaging, purposeful and multi-modal. More powerful learning comes from interaction and idea sharing that drives greater understanding and empathy. A great example is Newsela which enables all children in a class to engage in a debate around a single news article. Instead of children dividing up into reading groups based on their reading levels (which is also stigmatizing to low readers) or reading the “just right” text on their own — Newsela’s leveling engine outputs 5 versions of the same article so the whole class can debate together.

This type of integration is important not only because it enables deeper learning and collaboration, but also because our schools were founded with a decidedly civic function, and a democratic society expects much more than individual achievement. It asks us to graduate those who exhibit sound character, social conscience, think critically, are willing to make commitments, and are aware of global problems. To those honorable objectives I would add Nel Noddings argument for teaching care. In one of the most powerful books of the year Unfinished Business, Anne-Marie Slaughter argues that our society devalues those who care for others. If our schools are truly microcosms of our society, as John Dewey first articulated, then our classrooms must foster caring relationships between students, and this necessitates children learning how to interact in a kind and empathetic manner, while still getting an education tailored to their needs.

The most promising new school models go forward with the mindset that personalization will help achieve a constellation of goals — both personal and community — that are higher and broader, aimed at serving the larger, democratic society.

Keeping these goals in mind, I’m as excited as anyone about personalization. Far too many kids were left behind by the old model. However, personalized classrooms can be challenging to manage. That’s where technology plays a role. At Reach, we’re eager to accelerate the shift towards thoughtful, goal-oriented personalization by investing in technology tools that help teachers differentiate instruction and manage the demands of a classroom more attuned to individual needs. It’s a core investment thesis of our fund.

Personalization does not mean isolation, and it doesn’t mean sitting our students down in front of laptops all day. Personalization is a strategy that allows us to adapt to the needs of all children, preferably after they have had a powerful shared learning experience that motivates them to dive deeper into a topic or practice a new skill and thus bring them together. The best schools and edtech companies understand that technology and personalization are not the ends of education, but that they are merely means to help achieve higher goals- goals on which the health of our society and democracy depend.

Thank you to Diana Barthauer, Jim Lobdell, Shauntel Poulson, Wayee Chu and Esteban Sosnik for reading and providing valuable input.